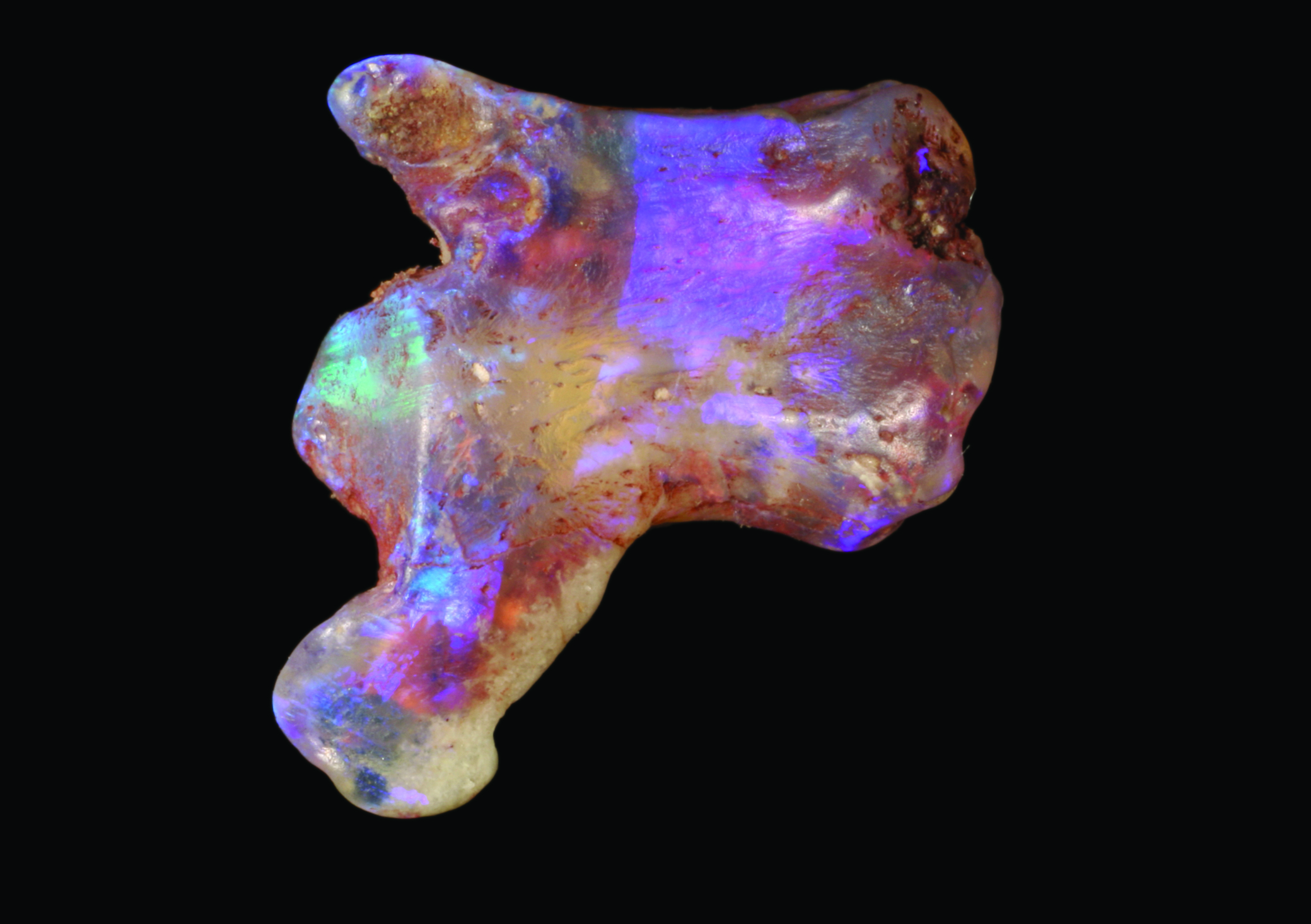

Cloaked in white powder and surrounded by vast plains, the city Lightning Ridge produces most of the precious black opal in the world. This rare gem, prized for its beautiful combination of color, hidden from view in the Australian outback in a town about 450 miles north-west of Sydney. And for more than 100 years, people have come to Ridge lucky enough to find opal hunting. As it turns out, these miners are not only revealing but opal opalescent fossils bones, rotated teeth, shells and plant material for Opal, immersed in the ancient hardened mud and preserved as gems, for 100 million years under a thin veneer of sediments. Some of the fossils found in the opal Lightning Ridge animal species found nowhere else represent, and are full of information from the Cretaceous period – the back of the dinosaur age. The prehistoric remains – some smaller than a fingernail – can be found onboard from my face or loading trucks slammed into piles of discarded Opal-bearing dirt, miners through. “If it were not for the opal miners – many of whom have acute and fossil eyes look so great a sense of wonder, have as a paleontologist – we would not have, or slightly above, learn about these fossils,” says paleontologist gemologist and long-term residents of the ridge, Jenni Brammall. could be invaluable as a fossil for science, the miners must be placed usually the first eyes on him, and this is a mystery miners Opal mining rights, which can always find Opal keep them in their recorded mineral claim, and It includes opalescent fossils. When money is scarce – and often does – a miner could be a fossil opal, in the hope of extracting salable destroy precious opal or sell the fossil abroad, where you can take a hefty sum. Sometimes they keep the fossils they find for their sentimental value, that hidden in private collections. For decades Brammall and a small group of peers who runs a fine line of the community to help them understand the value of opal fossils, urging especially rare artifacts to donate. A cornerstone of their efforts is the Australian Opal Center, founded in late 1990 and has quickly outgrown its small showroom on the main street of the city. The Center maintains the most diverse public collection of fossil opal in the world, mainly through the donations of accumulated Opal miners, many of whom give their findings Gifts from the culture program of the Australian government, which offers tax deductions for donors. But go, despite these efforts, countless fossil opal lost on the black market, pushed out of the reach of research institutions by the highest bidder. For this reason Brammall and his colleagues start their efforts, planning and an icon museum and research center will be built to the design of the historic area of Three Mile Opal out of town for the incomparable natural heritage to show the region. They also work to raise funds for the precious fossils found at the Ridge to buy so that it permanently in a public collection can be stored, accessible to both communities and researchers. The mining community, which is struggling with the current drought and always at the mercy of Opal buyers and their lively taste, recognize that things have to change, sustainable future for the city to ensure and are widely supported by paleontologists efforts . In line with the other residents, Barbara Moritz, who came in with a Lightning Ridge opal miner in 1990, says the new Opal Center “Australian may come soon enough.” Opal is commonly found around the world, but precious opal is very rare and geologists say nothing compared to that produced in Central Australia. opal fossils have also been found in other opal fields in Australia, but Lightning Ridge is characterized by the greatest variety of extinct freshwater conservation and land animals, including dinosaurs aplenty. One hundred million years, which is now dry interior of Australia was flooded by a huge inland sea and Lightning Ridge was in its path. As the sea retreated, it is the leading theory, exposed a strange mixture of sediments laced with minerals to form a reactive sandstone. Rocks closest to the surface began to time, to create a silica rich groundwater. E ‘state in cracks in the rock and filled all the voids between the skeletal remains of dinosaurs and other long-extinct creatures. Elizabeth Smith, a paleontologist who studied the opal fossils from Lightning Ridge for decades, has it all: shark teeth, turtle bone, lung fish, pine cones, birds, marine reptiles, as well as all kinds of dinosaur bones and teeth . The teeth are more revealing, Smith explained, in particular those consisting of so-called common opal, which lacks the opal brilliant colors can be, but translucent. “For the same scale anatomy end to see inside the tooth, teeth is really something,” he says. Smith was pulled for the first time in 1970 on the crest, long before the Australian Opal Center was a whisper on the horizon. Later he takes to live there permanently if opal mining exploded in the ’90s. While her husband digs for Opal, Smith was looking for fossils. Now, in addition Brammall work a way forward to find where opalescent fossils of the whole community will benefit. The couple speaks often and open with the opal miners to wonderous fossils of Lightning Ridge, in order to appreciate the people how special they are. And yet, says Smith, over the years, they have some “big” important fossils in private hands held saw or sold abroad. Talk to each opal miner, and they will be quick to tell you their treasures are fought. Opal mining is a grueling job, physically and emotionally, and “a good way to go very fast breaks,” says Kelly Tishler, a third-generation miner from Lightning Ridge. Miners usually work alone or in pairs, and many live off-grid cabins self-built or caravans on their mineral request, a small piece of state-owned or private, where the miners are for opal an exclusive license for the research and mine. Some supplement companies side to their income. Petar Borkovic as Outback Opal Tours runs with his wife. “But I’m an opal miner. And ‘in my blood,” he says, with a smile through the noise in Sheep Yard Inn, a pub in the middle of Grawin opal fields of Lightning Ridge Southwest. Before the Australian Opal Center in the city was, samples of interest that had been acquired by the miners were sent to distant natural history museums, including the Australian Museum in Sydney, where two of Lightning Ridge are the most famous fossil. Steropodon galmani galmani it found the first mammal from the Mesozoic in Australia, and kollikodon ritchiei the second. Taken together, they indicate the diversity of early mammals of Australia. These small samples, a little ‘more than an inch long, are immensely important, says Matthew McCurry, curator of paleontology at the Australian Museum. “They are the first representatives of mammals here [as] in Australia,” says McCurry, and when they were discovered, the oldest evidence of monotremes in the world. “Every Opal of immense scientific value champion” because it provides a unique window into the past in Australia, says fellow paleontologist Paul Willis, an associate professor at Flinders University in South Australia. Our imagination could with dinosaurs green light, which has traveled through the Jurassic and Cretaceous mammals, but proliferated during this time, the ancestors of Australian monotremes lay their eggs only, the platypus and echidna. Willis knows all too well how scientists happy and all Australians are these copies in public collections. As a PhD student at the University of New South Wales in 1980, it was that it had been dug up at random from opal miners in Coober Pedy in South Australia by the Australian Museum with the reconstruction of the fossil skeleton of a small marine reptile, a pliosaur, task. Eric, how pliosaur the nicknames, the most complete fossil skeleton of opal remains of invertebrates found so far, but came without ceremony in the museum in a box. A wealthy property developer had bought the skeleton and was paid to be ready for viewing. That is, until it went bankrupt. Suddenly Eric was up for grabs. A collection of public funds more than $500,000 Australian rake, so that the national treasure museum and can acquire expose him. It took considerable sums in a similar way to fix other fossil opalescent one-of-a-kind come so that they are properly recognized in public collections and protected for generations. The first mammal from the Mesozoic found in Australia, galmani steropodon galmani, purchased by the Australian Museum in 1984 as part of a collection of fossils opalescent opal dealer David and Alex Galman for AU $80,000 was. The second, ritchiei kollikodon, on its behalf, has had a price of AU $10,000. More than 80,000 people visit each year, the Ridge, a number that continues to grow. Many come specifically to see the fossils opalescent on display at the Australian Opal Center. One morning in late April, the showroom with groups of people piled in the windows hovering around. Many visitors who come to ask Smith Weewarrasaurus it all the way for dinosaurs to come up with Lightning Ridge and see the hope the new jewel in the heart of the collection. Just last year, a new species of herbivore dinosaur was described by an opal intact jawbone with some ribs teeth were found near Lightning Ridge. It ‘been Weewarrasaurus pobeni for opal dealer, Mike Poben that has designated the sample tingling in the Australian Opal Center generously donated after learning, by some miracle, in an opal miners bag crude from Opal Wee Warra Bought field. After meeting with visiting paleontologist Phil Bell, who knew immediately that there is something special Poben Bell he says the fossil decided to donate “around the world to make sure it was announced.” “In the city as part of the Community, with the opal center is absolutely essential to secure these treasures,” says Bell at the University of New England in Armidale, New South Wales, Australia. There is a very real concern among people in Lightning Ridge that their fossil remains materials to its original position, adds Smith. The community, he says, understand the scope of what was lost. “The material had come out of the ground all the time the miners were digging”, but the presence of fossils – and their scientific value – only the light gradually in recent decades. Brammall and Smith share fossil knowledge with the miners their experts, they bring them to the Australian Opal Center to ask for help to identify a sample, so miners, history, figure out who hold in their hands. The miners often outrageous ideas about what he managed to do what Smith says it’s all part of the fun, but every now and then, someone brings something “very important.” From her bag, which she calls a small opal tooth borrowed from an opal dealer. Smith believes there is a crocodile tooth but the unusual features has at its base out. It is photographed and then returned to the owner. “Regardless of whether it is in the collection, I have no idea,” he says. “We rely on the miners – and for them to do good,” says Smith. Oh, they continue opalescent fossils are sold on a daily basis as prized collection, and paleontologists are not able to restore it. The money is always the problem. to keep tens of thousands of dollars to dig sunk their savings in machinery and fuel, some miners are able to present the opalescent fossils and museums have for decades lacked the necessary funds spent, they had to acquire at fair prices. “We are losing our heritage, because we have this opal fossils have the means to fix,” Willis says. Export fossil opal from Australia without permission is prohibited under the protection of movable cultural heritage Act 1986, but more Opal markets outside Australia and a miner just to make ends meet may be looking for. In difficult times, things are not sentimental. “One thing about opal mines that you can not tell another Opal Miner, what with her [her] to Opal,” said Tishler, the field at Three Mile Opal toppled the rocky ridges looking out, one of the first fields for the area. A self-confessed “fossil Mother” Tishler says he has a private collection of fossils opalescent who wants to leave a legacy to the Australian Opal Center, but also to opal jewelry grandmother in times of need to sell. Brammall and focus Smith, not what is lost on what they can do for the Lightning Ridge community. “We win more than we lose,” says Brammall their efforts that begin with reference to the miners as the staff treated them with the respect they deserve. And ‘it is encouraging that a large opal fossil traces of the ridge, a collection of dinosaur bones, including the most complete dinosaur skeleton in the world’s opal came recently in the collection 31 years after it was discovered. In the future, a fund would be a means of acquiring the Australian Opal Center has not been able to respond quickly and need to rely on federal funding limited when these treasures in the offers are. But the first step has been to the world-class facility without supporting the growing Australian Opal Collection Center will host and display. It is hoped that the museum announces a new future for Lightning Ridge, one of the deep history of the country and heritage of opal mines identifies only the opalescent fossil celebrated new visitors prefer the secluded town during and a global hub long-awaited plans its science Opal and education. With the local funding, state and federal governments – and a significant contribution by the Community – the new center has, it will be by renowned Australian architect and construction gear designed soon. For Smith, the new museum a promise of long standing in the community. She knows of some fossils of great scientific importance outside in private hands, the other would agree “game-changing” in their respective fields. Smith, the sample held between views, tantalizingly close to believe that the new Australian Opal Center will encourage more people to share their fossil collections. “They want their fossils safe” Brammall says, “in a public collection, the opal fields.” Clare Watson, a freelance writer and Australian journalist specializing in science. His work has appeared in, among others, Australian Geographic Smith Journal and lateral magazines and broadcast on ABC Radio National (Australia). This article was originally published on Undark. Read the original article. Picture copyright by Robert A. Smith / Australian Opal Center

Related Post

First clone endangered Przewalski Horse Born in Conservation effort to save the species

The Przewalski's horse first successful cloned endangered was born on August 6 in an animal facility in Texas San Diego Zoo Global announced on Friday....

understanding inside the dangerous mission that tick and extremists Makes How to change their minds

On a cold early winter 2014, the American academic Nafees Hamid was invited for tea on the second floor of the Barcelona home of a...

How fear can spread like a virus

familiar sensations were: my rapid pulse, put on my chest, my attention narrowing. These were the feelings that I had many times in my life...

Remarkable Go sharks are here and strutting All Over Your Profile

Scientists have four new species of walking shark discovered the sea in some way to prove it can still seem a bit 'mysterious. It was...

An artist and activist Ohio is transforming the acid mine pollution in Paint

Sunday Creek starts from Corning, a small town in southeastern Ohio, 27 miles in front of the Hocking River downwind link. How much of the...

Exclusive: Chinese scientists have sequenced the first genome COVID-19 speaks of Controversies Its work environment

In recent years, Professor Zhang Yongzhen has produced results in thousands of previously unknown virus. But he knew immediately that this was particularly bad. It...