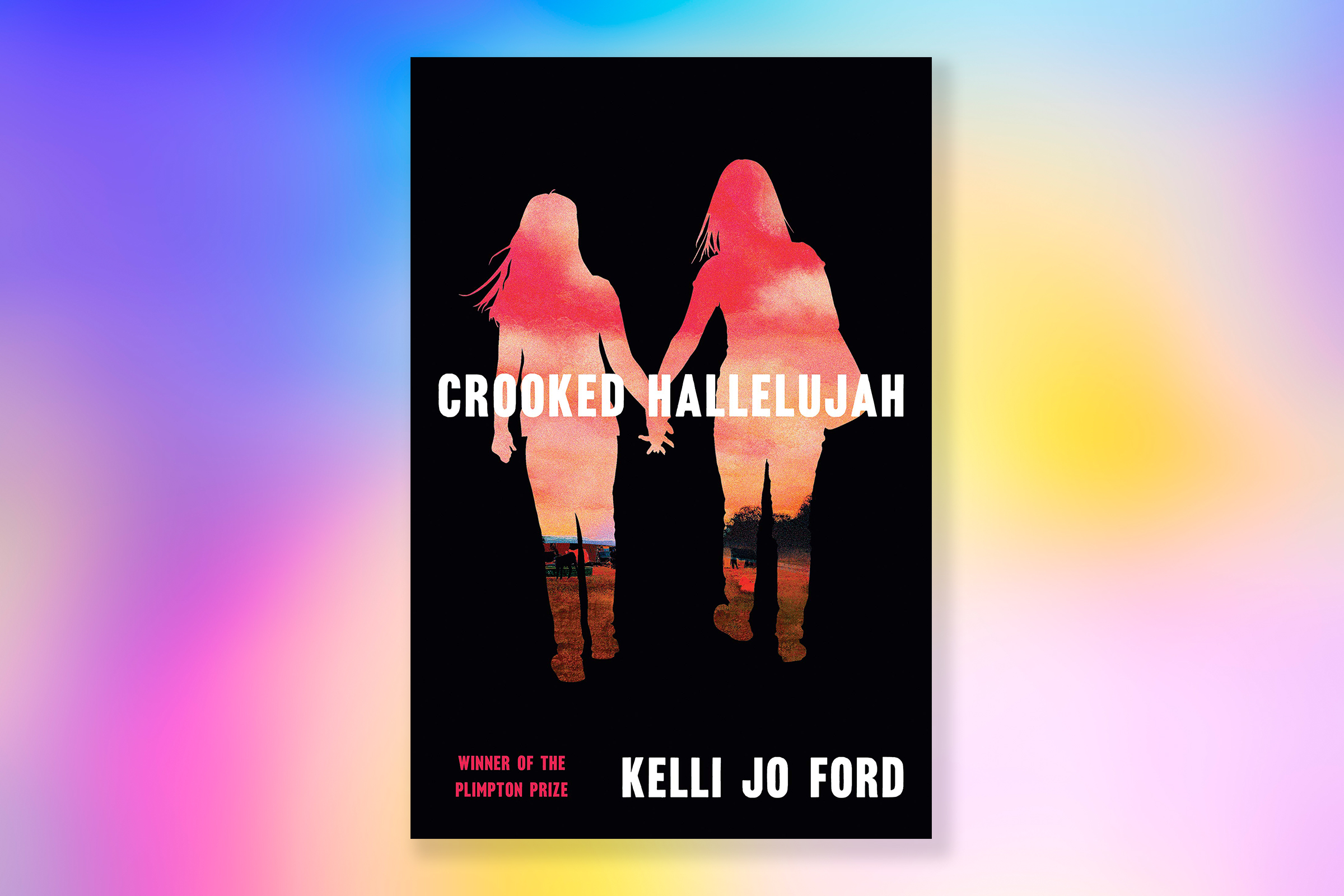

I pad around my house in the morning, on valves and turning lights me to ensure that the Apocalypse is closed is still more than a thousand miles to the door in front of my mother. Innovative This line in the novel Kelli Jo Ford Crooked Hallelujah debut is the last section of the book, modestly titled the “near future.” Up to this point, the book is a powerful, well-monitored family drama following the lives of four women Cherokee by members of their families force them from the Holiness Church, who have learned to structure their lives and self-esteem. Then comes a casual mention of the Apocalypse. At any other time in recent history, a change in the late apocalyptic genre of literary fiction may seem absurd. But now, it housed in a time when we expect not only a global pandemic, but also centuries of anti-black racism and pain to the surface, it feels true to. The end of the world that we all do not look at the time, how they experience having so many books, movies and TV shows. There are zombies or aliens; Not knowing, witty white men that enhance and save the day. There’s only us: fear, traumatized and galvanized, but has yet to endure the banality of life everyday as if all is well. And ‘our only: try to put aside the pain and anxiety enough to focus our past long for the pain and fear that our present. Ford, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, offers a novel in stories, so that they can move easily through viewpoints, history and time. Each chapter agonizing slowly added to the reader’s understanding of these women and their lives more difficult. And ‘the content of this life that deals with Ford novel. Grandma, Lula, Justine and Reney are fictitious Women Cherokee, yes, but as a true indigenous women, who have deeply affected by colonization and assimilation. Readers looking for a literary version of Edward S. Curtis painting will be disappointed; Crooked Hallelujah is no way for readers not Cherokee to get a taste of the Cherokee culture. What’s the whole point. The indigenous people have more and more that ordinary American literature places we need to be written. In the Ford world, like ours, we have Christianity to the indigenous communities for centuries, is forced by the first missionaries who have a devil worshiping heretics was felt with or through imposed by synonymous with indigenous government, the Indian residential school church school, the natives separate children from their families, robbed of their language and culture. Women from Crooked Hallelujah Cherokee Cherokee have their language and culture were too private victims of their other apocalypses survive their community had. This makes them somehow make it less indigenous. Their experience intergenerational trauma, poverty, violence, self-hate, religion and forced assimilation are well known to the natives who have written for the Ford clearly and with much love this book. What are your experiences with self-knowledge, love, joy, and finally release. “As a big old baby, I hurt for the girl who I was and asked that no disease would be without the Bible, without much loss of God,” says Justine a talking point not only indigenous experience, but perhaps all of us. “But without the things that make us who we are,” he continues. “We are nothing, I know,” Elliott is the author of the forthcoming book of essays, a mind of Earth Outreach Copyright by

Related Post

Sigrid Nunez new novel paints a beautiful portrait of grief and loss

And 'in September 2017, and a writer of middle-aged unnamed visited the College a conference. Her ex-boyfriend, an author, talks about the bleak future of...

I am a Muslim with a 11 Birthday September is Iranian-American is how I come out of My Identity

My ninth birthday fell Tuesday in September in a school day, a bright and clear-ski. I expected my mother treats to school to bring lunch,...

10 best TV teen drama of all time, ranking

With Labor Day in the back, it is once again the time when nerve student crowd usually their coolest new clothes at Monday painted corridors...

If one choose Unpregnant Spirited comedy about a woman’s right

In the years since Roe v. Wade, a woman, access to safe and legal abortion in the United States has felt increasingly precarious as if...

Poet Claudia Rankine on just us and the display of anti-Black racism of the Raw Truth

The author and poet Claudia Rankine witness the bland collective reaction after James Byrd Jr. was dragged to death along a dirt road in Texas...

The Tuscan countryside deserves top billing Liam Neeson father-son drama Made in Italy

It can only go out with a certain film campaign on his sandwich, a couple of stunning views fat dishes with a slice plot born...